Chapter One: Discoveries

Bert Parmaster had been engaged to haul rubbish from Salvation Army Maternity and Rescue Home at Des Moines, Iowa. He began this task about three o’clock on the afternoon of 4 April 1916. From initial wagonload, dumped that Tuesday at Southeast Sixth Street bridge, the site’s Dump Master discovered an infant’s body.

According to Des Moines Register and Leader front-page reporting, the pair “hastened in pursuit of the driver of the wagon and overtook him.” Parmaster disclaimed any knowledge of having hauled dead baby to dump site: he was, however, able to point investigators to place where debris had piled ... along east side of Rescue Home barn.

|

| Images enlarge when clicked. |

Police in 1916 called Claude H. Koons (c1888-1917, left), Mortician for Patrick, Selover, Knight & Hamilton. Koons was in second term as Polk County, Iowa Coroner.[3] He apparently observed crime scenes and saw remains removed to the funeral parlor.[4]

English-born Salvation Army Adjutant Edith E. Dennis (b. c1863), Superintendent of the Home, declared “after viewing the body that she could throw no light on the child’s identity.[5] She said it was her belief that the body had been left on the rubbish pile Sunday night by some woman who wished to dispose of her child.” This may have been based on observations lent by Captain Alice Morrow and Ensign Ida Alhstrow, also employed at the Home: they “heard a horse and wagon, back of the barn, shortly after midnight Sunday night,” and were “of the opinion the body was left by the person driving the wagon.”

Washerwoman Rosina Theresa ‘Rosa’ (Gash, Miller) Barton (1881-1956, right) greatly advanced investigation. Austrian-born Barton accompanied police officers and a Register reporter, and “positively identified the blanket in which the child was wrapped. She said the blanket belonged to Mrs. Anna Duty, who stayed at her house for several weeks. She is the wife of Ben Duty, a laborer.” (The itinerant pair did not own horse or wagon, however.) Barton was firm: she declared couple “constantly were quarreling.” She informed that the husband had threatened to leave his wife if she did not get rid of the baby. “It became so that I could not stand it any longer and I had to ask them to leave. They neglected the baby and I believe the child starved to death after they left my house. I am positive the baby in the undertaking establishment is the same child.”

Barton provided crucial but daunting leads. “The man said, when he left, that he would ship one of his trunks to Chicago and the other to Minneapolis.”

The Evening Tribune at Des Moines incandesced in later edition. Front page, column 1 headline decried “NURSES LEARN IDENTITY OF BASKET BABE.” By their account, “Little One Found Dead at Army Rescue Home” had been “FOUND ONCE BEFORE IN STARVING STATE.”[6] (I never found authorities referencing a basket; the child – initially, at least – might have more logically been bruited as 'Blanket Baby.')

And, where there is heat, might also be enlightenment: Miss Adah Louisa Hershey (1880-1947), Superintendent of Des Moines’ Public Health Nursing Association, with Miss Minnie M. Bush, Assistant Secretary for Associated Charities of Des Moines, described 18 March “rescue which resulted in saving the little one from starvation.” (Eighteen days earlier.)

On advice from the Polk County Physician, nameless infant of undisclosed gender had been taken to Iowa Methodist Hospital (right). It was discharged 25 March “as strong enough to be cared for at home by the mother. Nurses at the hospital … said the baby gained several pounds during the week it was there and was able to assimilate its food. Mrs. Dudi, say the nurses, frequently visited the baby and displayed sincere motherly affection.”

“There can be no question about the identity of the Dudi baby,” Nurse Hershey pronounced. “I believe the mother really loved the child but the father did not want it and said he would not live with his wife if she kept the baby.”

C. M. Young, Secretary of the Iowa Humane Society, had occasioned a grand jury to try facts on Ben Dudi’s alleged desertion.[7] Indictment had been returned. According to this report, husband and wife had been arrested on complaint filed in Juvenile Court. “They were charged with willful desertion, the mother being accused of purposely failing to care for her baby.” No adjudication was described.

Perhaps credit for doggedness is due Des Moines Police Detective Roy J. Chamberlain (1888-1968, right). Chamberlain subsequently traced his quarry, “by means of their baggage, to Chicago. He arrived there after they had left but discovered that the pair was in Minneapolis and expected money from a relative. He then wired the Minneapolis police, who took the two into custody at the St. Anthony Falls bank” on 8 April. The Minneapolis Journal reported Chamberlain arrived at the Twin Cities the following day, to extradite Mr. and Mrs. ‘Bergen Dude’ “to face a charge of strangling their six-weeks-old daughter, Rose.” The tale had grown even more sordid: “It was first believed by the Des Moines police that the child, in a weakened condition, had been tossed on the heap to die of starvation. Investigation by the coroner [Koons] is said to have indicated that the baby was strangled.” Chamberlain may have been emotionally invested: the former Minnie Shicker (1888-1964) was due to deliver their first child, daughter Margaret, on 10 August.

The Minneapolis Morning Tribune declared the dead baby girl was named ‘Rosa.’ As for identification, it wouldn’t be until 13 April that the Journal would cite records sufficient for me to identify defendant Bolesław ‘Ben’ Duda (1884-1963). Wife was depicted as Anna (Garbacz) Duda. (‘Mrs. Anna Duty,’ above.) I, perhaps mistakenly, believe spouse to have been Rozalia ‘Rosa’ (Rudnicki) Duda (b. c1887), mother of baby Rosa.[8] By then the English-language-proficient but not-yet-naturalized Catholic Poles in Des Moines jail had legal representation.

Brothers, partnered Minneapolis attorneys John P. Nash, Jr. (1881-1922) and William M. Nash (1882-1934, right), mustered a defense. [9] Minneapolis Health Department record had certified an infant death, 2 April. (Two days prior to discovery of Des Moines corpse.) Attending Minneapolis Physician (Iowa-born) Richard James Phelan (1876-1925) “gave a description of the father and mother, which tallied with that of the prisoners taken to Des Moines.” Dr. Phelan had pronounced “bronchial pneumonia was the cause of death,” in Minneapolis Tribune reporting.[10]

Three Des Moines witnesses had identified body there as the Dudi baby. Three witnesses in Minneapolis averred Duda baby had been interred northward. Chillingly, Koons proposed “The only way to settle it, is to take the Minneapolis body to Des Moines, lay the two side by side and have all the witnesses look at them.” Press frenzy at Des Moines thrilled at macabre prospect.

On 13 April the Polk County Attorney ‘demanded’ Minneapolis cadaver be exhumed. Koons arrived at the city two days later … with or without the Basket Baby’s corpse. Hennepin County Coroner Gilbert Carl August Seashore (1874-1951) promptly authorized Minneapolis disinterment.[11]

“The grave was opened in a drizzling rain late yesterday, five days after the body of Rose Dudi was buried at St. Mary’s cemetery, April 3,” reported Sunday Journal ... from front page at Minneapolis, 16 April. With Koons were Dr. Phelan, attorneys Nash, reporters, and no doubt morbidly curious onlookers.

“Resemblance between the exhumed body and that found on the refuse heap at Des Moines is so close Coroner Koon said that he readily understood how those who confused the two arrived at their conclusions” the Journal announced. The Tribune at Minneapolis contended Koons finally, on 17 April, “wired the chief of police and county attorney at Des Moines to release Ben and Anna” ‘Dadi.’ For all the errors he’d made, in the Basket Baby’s date and cause of death, Mortician Koons (and justice delivery) might have benefitted from forensic tutelage by Dr. Seashore.

To his credit, Koons had informed the Sunday Journal “I shall not only ask the dismissal of the charge against Mr. and Mrs. Dudi, but I shall ask the Des Moines police to begin [immediate] investigation to determine whose baby it was which was found.” The grieving Bolesław and Rosa returned with two surviving children to New Jersey, to live out their days in proximity of his brother Stanisław Duda. Likely without bidding adieu to former landlady Rosa Barton or meddling neighbors.

Chapter Two: Revelations

Let us return to scene of the crime. Zeller found “The [Salvation Army Rescue Home at Des Moines] in 1917 cared for 81 girls and 71 babies. Of these, 56 babies had left the hospital and five had died [SIC]; a very good rate of success for the times. Seventeen girls and ten babies were typically under was its care at any one time.” The enterprise was surprisingly well endowed. Also, Army brass proved sophisticated in charity-legislative initiatives. Zeller documented deft property trades, and not only close operational ties with other agencies … but capacity to roll out services under female administration. The Rescue Home had been electrified, an operating room added in 1912. Maternity for unwed mothers was impressively addressed charitable concern in Des Moines.

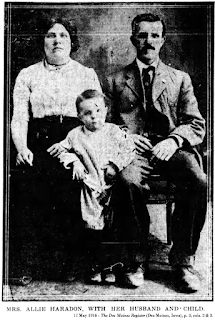

Allie Belle (Moore) Haradon (1889-1962) was described as “a large woman with kind, motherly face” in 1916. Born at Cass County, Iowa, a Des Moines Justice of the Peace had, in 1908, married nineteen-year-old Allie to Teamster William Warren Haradon (1874-1929). A divorcé, his second foray into married life was to a girl fifteen years his junior. Haradon had survived his father … wounded, Union Civil War Veteran Samuel O. ‘Sam’ Haradon (1839-1903). Eldest of three surviving sons, William lived with mother Nancy A. (Meader) Haradon (c1852-c1932) until attaining his mid-thirties. Allie, firstborn of Day Laborer Jacob Theodore Moore (1859-1946) and the former Maggie Lena Robinson (1869-1946) had seventh-grade education … and was likely to have been the more educated in her marriage.

Allie had given birth to Harold Laurence Haradon (1910-1985). By the time family tableau (right) was rendered, William Haradon had labored along in freighting wagons at Des Moines for several years.

Allie had, in February 1916, placed classified advertisement in the Des Moines Register and Leader. She was intent on adopting a girl child. By Register finding, a “baby was adopted from the home of Ernest and Emma Ohrtman of Bagley,” Iowa on 6 March. Allie “brought it straight to her home in Des Moines.”

And the story fractures into scenarios.

‘W. W.’ Haradon informed the Register “he and his wife decided after she had brought the baby to their home that they could not raise her conveniently and it was decided to give her away.” Evening Tribune followed with variant, emotive frame: “It was the husband who, police say, first objected to the adoption of the baby, and the police believe that Mrs. Haradon’s great love for him might have driven her to desert the child after keeping it for only a day.” The Sioux City Journal from some distance contended Mrs. Allie Haradon “had adopted it from a woman at Bagley, Ia., but says it was unhealthy and she decided not to keep it.” I’m struck by genderless references. And immediacy of Wagoneer William Haradon’s reaction.

Dormant following Dudas’ exoneration, front pages of Des Moines papers blossomed with news that Allie was arrested 16 May. In the Haradon home.

I conject Allie had transited from subtler disquiet while Dudas were under investigation. She reported sleepless nights after their release. Phantasms may have been harrowing, indeed. The twice dismissed infant had not been laid to rest. Koons retained evidence at the ready, in morgue at the Polk County Courthouse. Allie was transported to Des Moines City Jail.

Though two other detectives took up the case, no revelation on how they came to put themselves on Haradon doorstep was made public. I suspect Allie could not contain herself. She gave up her secret to another. Reporting made it clear she was astoundingly inclined to confess … and seems to indicate she only came clean with William once she had been jailed. For all I know, the divulgence had been pre-arranged. More than one paper concluded with “Mrs. Haradon said that her husband had nothing to do with the death of the baby,” drawn from her confession. Under subhead ‘Woman Conscience-Stricken,’ the Register related “About April 5 my husband told me that some man had found a baby on the dump. I made up my mind it was the baby I had abandoned. I read nearly all the articles in the paper about Ben Dudi and his wife being arrested for killing this baby. I thought at the time I should give myself up and stand punishment for what I had done, but on account of my husband, parents and little boy I could not do it.”

For his part, W. W. confided to Register reporter on 17 May “I supposed my wife had given the baby away, and dismissed the matter from my mind. Not until today did I dream that she had abandoned the child.”

While backing off from confession to abject murder, Allie’s account of events did not waiver from initial story-telling. Affidavit following arrest anchored her into it: “I took it to a shed near the Salvation Army home. When I left, it was nursing the bottle. I supposed the Salvation Army people would find the baby and give it a home. When my husband came home from work, I told him I had given the child away. He asked me what name I gave the people.” Allie replied she had not named the infant, and that “I abandoned the baby March 7 and have not seen it since.” Remorseful by all accounts, Allie claimed responsibility for a death. Overwrought, she had been signatory to document interrogators had constructed.

By Allie’s disclosure, the infant died between 7 March and Dump Master’s ultimate discovery of the corpse on 4 April. I sense four weeks to be extraordinary interval. (Inexpert Koons reported the baby dead a mere twenty-four hours in postmortem analysis.) I can readily imagine Allie would not expect confirmatory reporting on foundling taken into Rescue Home in near-monthlong interim. Until cadaver’s revelation, I suppose, she could have contented herself.

She had known of tragic outcome from her March decision – not to reveal shame-tinted predicament to Salvation Army staff – for forty-two days. Duda parents had unconscionably been under disgracing suspicion of murder for thirteen of them. They too quite likely fostered deep concern for their children ... rendered parentless in transit, following loss of a sibling.

Des Moines Detectives reached out to German-born Ernest Otto Heinrich Ohrtman (1877-1922) … and ‘wife.’ From Register reporting on day immediately following arrest, one discerns investigation by Detective Thomas Roy Pettit (1891-1962) and Officer George Ferdnand ‘Fred’ Trimble (1875-1933), left, had been ongoing prior to their apprehension of Allie Haradon. Mailed intel must have been several days in exchange prior to 17 May receipt: “In reply to an inquiry made by Detective Chief James McDonald, a letter was received from Mrs. Ernest Ohrtman, asking if the baby was getting along all right.”[12] Correspondent seemed unaware inquiry was linked to a child’s remains. To outrage prominent in clangorous reporting for a month. “Mrs. Ohrtman said the child did not belong to her but to her husband’s first wife.” The former Lavina Johnson (1883-1954) had, in 1914 at Pomeroy, Iowa, sued Ohrtman for divorce.[13]

When questioned by telephone, Ohrtman – supporting himself at Yetter, Iowa the day following Haradon confession – confided to a Tribune reporter he had no plans to go to Des Moines. “Why should I?” he asked. “The baby is not mine.” (Present tense? Infant remains were two months and eight days old.) “I got rid of the woman, and then I didn’t see why I should should keep it.” Ohrtman let it be known “he was divorced from the mother of the child about a year ago, and did not know who its father was.” In questionable assertion, Ohrtman “said his first wife, not he, gave away the baby, and he simply signed the contract with Mrs. Haradon to please her.” I note William Haradon could not be bothered to witness this undertaking.

Under headline ‘Woman Adopts Baby And Then Kills It,’ scant, two-paragraph notice of Mrs. Allie Haradon’s confession appeared, page four, in The San Francisco Examiner 17 May.

Allie was taken before tall, slender Municipal Judge Joseph Ethan Meyer (1882-1960) on 17 May. His only child was a daughter who would celebrate second birthday the following day. “Will you plead guilty to a charge of murder?” he enquired. Only Judge Meyer’s clerk, Policewoman May Goddard and three reporters observed as Allie trembled visibly and “could barely stop her tears.”

“Murder?” the prisoner no doubt gasped. In recoil, “… as if not understanding,” according to Evening Tribune report. “I didn't murder the poor little baby. I just left it in the vacant building.”

“It was as if she couldn’t comprehend what was going on …” “After Mrs. Haradon had haltingly denied the charge of murder, Judge Meyer asked her how long it was between the time the baby was found and when she had deserted it.”[14]

“The little baby was there a month,” acknowledged Allie. “Then she broke almost completely.” The mournful attestor pleaded “I want to see my husband before I answer any other questions.” I surmise, by William’s absence from proceedings, he abandoned Allie. That, if she were reading newspapers, it was medium by which the couple had been communicating.

Meyer charged the defendant with murder, bound her over for a Grand Jury to try. He ordered the twenty-six-year-old mother held without bail. Allie, who had reportedly been styled ‘The Woman of Tears’ by City jailers and detectives, was immediately transferred to Polk County Jail … across 6th Avenue from infant victim in the morgue.

A distinctive ‘Mrs. Ernest Ohrtman’ was certainly in circulation. The Des Moines Register and Leader quoted from communique sent by a purported twenty-year-old at Yetter thus styled. (Lavina was likely age thirty-three.) It was apparently Emma who wrote Scots-born Chief of Detectives MacDonald (1867-1927, right). This letter arrived 18 May. She presented as indignant while both self-centered and in close association with her man: “We cannot understand why she murdered our innocent baby. If she didn’t want my baby why didn’t she return it? She didn't have to keep it if she wasn’t satisfied with it.” Emma resolved, of Allie, “We want her to suffer for the awful crime she has done, if she is guilty.” I suppose Ohrtman’s purported second wife intended damage control, to preserve social standing amidst tawdry, public approbation for having birthed unwanted child: “It is impossible for us to come to Des Moines and look after it, as my husband has several men working for him … working every day to make an honest living.” I am reluctant to judge other’s grief, but Emma too seemed to indicate a corpse might require looking after. She and Ernest had probably been asked for burial intentions. For baby they had obligated to another.

German-language Tägliche Omaha Tribune reported on Herr Ohrtman, Frau Allie Haradon and ‘Heilsarmee’ (Salvation Army) on 20 May. Their correspondent was sufficiently informed to relay that Red Line Transfer Company employed Frau Haradon’s ‘Mann’ William.

Salvation Army Commander-in-Chief for Western States, Thomas Estill (1859-1926), astutely conducted Iowa-Nebraska Congress over long weekend at Des Moines, 20-22 May. Well-attended, public meeting (featuring Songster Brigade) facilitated “united demonstration” intended to reset Rescue Home in favorable community regard. Finance Board activity had been impressive prior to scandal: regular luncheons among socially elite women were punctuated with annual fete, Thanksgiving recital, rummage sale and ‘Melting Pot Committee’ converting statewide jewelry donations to operating funds.

A Register and Leader reporter – apparently new to the story – was allowed to look in on “Mrs. Ollie Haradon, foster mother of the “basket babe,” abandoned on a city dump where its lifeless body was later found.” The story’s subject “sits in her cell at the county jail and spends her time weeping and brooding.” 22 May reporting had soft edges: a subhead admitted “Mrs. Ollie Haradon Has Excited Sympathy of Jailers.” Six days in custody, a bereft Allie had not engaged legal counsel.

On 1 June, by 3-2 vote, Polk County Board of Supervisors allocated $500 from pauper fund to Salvation Army Maternity and Rescue Home at Des Moines. In consideration of care said Home would give indigent maternity cases sent there by proper authorities.

The following day a Polk County Grand Jury returned indictments against Allie: for murder in the second degree and ‘exposure of a baby.’ Observe (left) “She Is Charged With Abandoning Famous “Basket Baby”” in Register and Leader sub-headline. And consider what engenders fame. “Basket Babe” appeared in brief copy trumpeting jury decision. I do not know whether Coroner Koons’ determination – that Dudas’ daughter was strangled – carried over to Haradon accusation.

Allie was arraigned before Ninth Iowa Judicial District Justice Hubert Utterback (1880-1942) on 3 June. Represented by Attorney James Morgan Parsons (1858-1937), she entered plea of Not Guilty to all charges. Parsons, interestingly, had been orphaned at the age of ten.[15]

“One of the most baffling cases ever brought to the attention of the Des Moines police department” was scheduled for trial at the end of September. Des Moines Register and Leader reporting imbued Chief of Detectives MacDonald and Coroner Koons with noteworthy forensic capacity: initially described as ‘blanket,’ the pair determined the baby’s corpse had been swaddled in a piece of white cloth. They detected the shroud “torn from an old tablecloth in a restaurant at Herndon, Iowa.” A mere five miles due East from Bagley site of contract for adoption (and nearly a hundred miles East-Northeast from Des Moines). Further, “Women in the restaurant described the woman to whom they had given the cloth to wrap around the baby.” It seems the near-newborn had been close to naked in conveyance (never did transaction appear as exchange, that Allie paid for the child); one wonders whether rural women stirred themselves in response to abject neglect of an innocent … or whether Allie had presence of mind to pause and organize a babe’s preservation from early March vicissitudes.

For murder, the accused faced minimum sentence of ten years’ confinement to ‘Female Department’ at Anamosa Penitentiary (left). If found guilty on the charge, Utterback had discretion to commit Allie to conclude her life in prison.

War in Europe seized press attention. Space allocated Allie’s plight evaporated beyond Iowa. Quarter-page column on page three contended Allie had been “put through the third degree” before confessing. The Register’s tone was less damning than it had been. First sub-headline alerted to “Foster Mother of Mystery Babe.” As if the pair had bonded. ‘Mothering’ opportunity had not persisted much into second afternoon of foster care.

Murder charges were dropped. Concluding first column on second page of the Evening Times-Republican at Marshalltown, Iowa delivered relatively sparse, 30 December notice: “Another chapter was written today in the basket baby murder mystery.” I did not find any Des Moines papers reporting on culmination of The State of Iowa vs. Allie Haradon.

Trial had that day been conducted in Utterback’s third-floor courtroom at elegant Beaux Arts Polk County Courthouse (right). A Trial Jury found Allie guilty “on a charge of exposing a child” and Utterback from his perch handed down five-year sentence. Evening Times-Republican headline read “Woman to Anamosa,” but Parsons personally signed $2,000 bond. This concluding record I was able to find on the matter reported “Her case is now before the parole board and it is believed she will escape a prison term.”

William ‘Waren’ Haradon (his signature) registered for military conscription 12 September 1918 at Des Moines City Hall. He gave Allie ‘Bell’ Haradon at Caldor Avenue residence as nearest relative. Allie was enumerated with William W. and nine-year-old son Herald Haradon at Caulder Avenue in 14 January 1920 census record: surely parole board appeal would have been litigated by then.

William was near thirteen months dead when forty-year-old Allie was taken to Broadlands Hospital by police ambulance 8 June 1930. She had fainted after pleading guilty to double-parking. Des Moines Tribune-Capital notice did not associate her with Basket Baby or murder.NOTES

Floss LaVerne (Haradon) Hardesty (1895-1967) was (Allie’s age peer and) paternal grandmother to the author. Sharing descent from William Warren Haradon’s great-grandfather, ‘Flossie’ was second cousin to William … one generation further removed from common ancestor. I thought it unlikely the pair were cognizant of one another. Yet the Queen City Times, at Agra, Oklahoma reported 13 January 1916 (four months prior to Allie’s arrest) that Flossie’s father “is here from Iowa.” Flossie, almost assuredly then at Agra, had in 1905 been enumerated in paternal grandfather Orlin’s household at Early, Iowa. (The town formed around smithery that brothers Orlin and Eli Haradon, Jr. established, 1875.) Early, Iowa was but fifteen miles from Yetter … where admittedly transient Ohrtmans appear in above account. Sac City, where many of her father’s maternal and paternal kinsmen farmed in 1916, was (their county seat and) near midpoint between Yetter and Pomeroy … twenty-five miles distant. Both were places of Ernest Ohrtman residence. I deem it highly likely that Sac County, Iowa Haradons alerted to a cousin of their surname become so prominent in Des Moines reporting. The Queen City Times noted Flossie’s father in return, 28 September 1916 visit to Agra: I now assume word of this sordid affair filtered down to my grandmother.

[1] Firstborn brother to Sergeant Delmege (right), Frank Raymond Delmege (1873-1909) had been a Des Moines Police Detective when shotgunned to death in attempted apprehension of a suspect. BACK [2] Jury decision was 9-3 for conviction of West and Beattie: prosecutors declined to retry the case and the pair – likely blameless – reportedly adjourned to ‘Old Mexico.’ (Both were enumerated at Des Moines in 1920 census.) As for anti-vice crusade, Iowa General Assembly introduced statewide prohibition: alcohol ban had gone into effect 1 January 1916. BACK [3] Coroner Koons, “youngest man ever elected on the republican ticket in Polk county,” according to his obituary, would die four months after Haradon verdict was rendered. He had been compensated $100/month, slightly higher than some of the investigating officers at Des Moines, and outside of income acquired as Embalmer, Mortician. BACK [4] Koons in 1917 complained Polk County morgue was “a useless thing.” He averred the chamber, without ventilation or running water “… has been used only once since the courthouse was built” eleven years earlier: “The body of the 6-weeks-old girl, adopted by Mrs. Allie Haradon and later found dead on an ash pile, was brought there for examination.” BACK [5] Matron Dennis, single and boarding at the Home, reported annual income of $216 for the year 1914. BACK [6] See Des Moines Register reporter William H. ‘Bill’ Millhaen, Sr. in Wertsch for World-War-I-era changes in editorial policy: “We built up feature stories as well as crimes of violence and tales of misfortune. If you could tie into a big headline, the paper would sell,” particularly among street-vending paperboys. “We manufactured headlines that would sell papers on the street.” After 1916 prohibition settled into place, 'Basket Baby' murder displaced simmering and months-running dispute over Mayoral decision to ban the film Birth of a Nation as distribution was scheduled to rotate to Berchel Theater at Des Moines in April. I was suprised by Grand Army of the Republic veterans publicly contentious in opposition to racially disparaging messaging. BACK [7] I believe C. M. to have been the extraordinary Clarence Marshall Young (1889-1973, right). Raised in Des Moines, preceding Yale Law School degree with Drake University diploma there, he would be one of five enlisted in Aviation Section of the nation’s Signal Reserve Corps to be sent, 1917, to train to pilot tri-motor Italian Caproni bombers. Shot down and captured the following summer, Colonel Young would serve in Hoover and Roosevelt administrations, regulate commercial aviation and retire as Vice President of Pan American World Airways. ‘C. M. Young,’ Secretary and ‘Humane Officer’ of the Iowa Humane Society, in 1931 successfully appealed adverse Polk County decision of 1928. On 30 January 1928, Dugan v. Midwest Cap Co. (wherein Young, under authority of the county’s Insanity Commission, had issued warrant then being contested for merit) had been dismissed for plaintiff’s failure to appear for trial. On 1 February 1928 – two days later – dashing aviator Young sailed from San Francisco aboard S. S. Maui for Honolulu. BACK [8] 1918 draft record registered a Boleslaw Duda (b. 1884) of medium height and build, with brown eyes and black hair. At Irvington, New Jersey. Spouse appeared as ‘Rosalia.’ Daughter Sofia (b. c1907 at New Jersey) had been enumerated 1910 with Bolesław (b. c1885) and ‘Rosa’ (b. c1887, married 1907) on mortgaged farm in rural Slavic community at Wisconsin. Per 1920 census, Sofia had been joined by brother Edward Duda (1912-1981), also New-Jersey-born: the family had returned to Newark environs there. I contend Sofia and Edward were alive and likely in traverse when sister Rosa died at Minneapolis and parents were incarcerated. Bolesław and spouse Rozalia were deemed literate in 1910; they had immigrated separately shortly after turn of the 20th century, were naturalized in 1917. Sofia and Edward may not have been left shiftless at Minneapolis. I found three others surnamed ‘Duda’ thought to be interred in Catholic-consecrated Saint Mary’s Cemetery ... all born between 1888 and 1897. They would have been in late teens to their twenties in 1916. Confoundingly, I note Find a Grave memorial not associated with any marker, for Mary Anna (Garbacz) Duda (1897-1953), maiden name identified in Journal reporting. BACK

[10] Dr. Phelan’s son Richard B. would succumb to disease, age nine in 1920. By alumni association account, the 1903 University of Minnesota Medical School graduate died of injuries sustained in 1928 “jump from window.” BACK

[11] Iowa-born Seashore (right) ran for Hennepin Coroner in 1908. “My first day in office satisfied me that I had stepped into an awful mess,” the death-certifier later recalled. “That day the new coroner had seven calls, including the case of a suicide victim in whose pockets Dr. Seashore found a handful of cards advocating his election.” Governor Burnquist would appoint Seashore Acting Hennepin County Sheriff in 1920 anti-corruption remedy. BACK

[12] Chief MacDonald was in 1916 father to three daughters, ages twelve to nineteen. Per obituary, his twenty-year police career ended in 1924. BACK [13] See The Pomeroy Herald, 15 Sep 1949, p. 8, col. 1 for 1914 retrospective. Ernest apparently acknowledged son Harry Leroy Ohrtman born to Lavina in 1912. Two of the couple’s three purported children were born following the House Carpenter’s 1908 bankruptcy. Ohrtman can be distinguished from William Haradon by 1912 Evening Times-Republican report … that Ohrtman’s automobile “became unmanageable” at Pomeroy depot. “The auto disputed the right of way with a freight engine.” Haradon apparently drove regularly for transport companies, was at the time likely considered a proficient horsecart driver. Ohrtman’s 1922 Lake County Times death notice (at Munster, Indiana) bore headline ‘Bitter End.’ Beneath: “Efforts of police to interest [friends] of the dead man in the east to provide decent burial proved unavailing.” BACK [14] Attorney ‘Joe’ Meyer had been on Des Moines municipal bench but two months. The Bystander at Des Moines, “The Best and only medium that reaches the colored people of the middle west,” had given him affirming front-page press in March campaign. Inquiry for length of time passed may allude to considered prosecutorial scenario whereby the baby had been killed before any could witnesses it within Haradon’s custody ... and late-night wagon had indeed transported long-dead body to Rescue Home just prior to 4 April discovery. Four-story Masonic Temple of Des Moines had been raised, 1913: Meyer was in elevated rank of brotherhood assembling there … as were members of Des Moines Police Department with best prospects for career advancement. Attorney Parsons, who would become Chief Justice of the Iowa Supreme Court, would be interred at Des Moines Masonic Cemetery. As would Detective Chamberlain and Chief of Detectives MacDonald. BACK [15] Drake University Graduate Utterback (Class of ’08) had been elevated from Judge of the Des Moines Police Court (1912-1914) in 1915. He had, at time of trial, apparently not yet become President of the Iowa Humane Society. Parsons matriculated from Iowa State College (Class of 1876). By New York Times obituary he left Civil Engineering at Cornell University to read law ... after taking satisfaction in settling legal dispute. Another biographer asserted ‘Jim’ Parsons had prevailed over his legal Guardian. BACK