2019 post Wild Confusion in Every Direction opened with “terrific explosion” of 1862. One-ton steam boiler launched with sufficient velocity to crash down through roof of adjacent, three-story warehouse belonging to Haines, Hardesty & Co. at Malvern, Ohio. I bookended winding blog post with concluding reference to “Blast Followed By Pandemonium.” Hardesty Chemical Company explosion gravely rocked Dover 4 May 1949. Speculation that firms’ ownership sprung from Hardestys sharing close kinship was overreach.

|

| Images enlarge when clicked. |

1917 draft record made me privy to Couzens as middle name. And that our subject’s eyes were gray, hair was brown. William, in his own hand, presented as (‘Hardesty’ and) Sales Manager for Philadelphia-based General Manufacturing Company.[3] He had married Elizabeth L. Heck (1891-1924). And declared her, their two daughters and an unidentified brother dependent on him.[4] William C. Hardesty manifest as ‘Private Secretary’ to Philadelphia Meat Packers three years later. He, Elizabeth and daughters were resident in his own, mortgaged, Philadelphia home.

Second daughter Ella Marie died 1920 … of bronchitis and having just attained age three.[5] William’s paternal grandmother, Margaret (Talbot) Hardisty (1835-1922) expired two years later. At Washington, D.C.Influenza took Elizabeth in 1924, at tender age of thirty-three. She was survived by William, daughters Elizabeth Louise (1913-2004) and toddler Vivian Elizabeth (b. 1919). Mother Elizabeth was interred near Ella Marie at West Laurel Hill Cemetery … noted for imaginatively designed landscape on Schuylkill River north of Philadelphia. [NOTE: Pedigree Chart concludes this post.]Our subject was depicted as managing candle manufacturing at New York in 1930 census. We discover only son of a firstborn son, of a firstborn son, in mobility upward and toward opportunity. William had remarried … to Philadelphian Mary Elizabeth Pierson (1897-1998). The foursome took up fashionably modern conveniences at Biltmore Hotel Apartments (right), Pelham Manor, Westchester County, New York. Haynes described trajectory at birth of oleochemical industry: “W. C. Hardesty Company, Inc., was established Oct. 1926 … solely for the production of fatty acids.” Recall Hardesty’s stint with Philadelphia meat packers. “The fatty acid industry of that day was undeveloped. Some fatty acid manufacturers were controlled by packing-house interests, which thus created intracompany consumers of the fats and tallows from packing houses; others also made soap or candles and consumed much of their own fatty acids.” Hardesty, who claimed but secondary education, “… was enthusiastic about the potential possibilities of this industry.” No doubt proffering work history of business recordkeeping, sales and executive management – while demonstrating some imaginary thinking – he secured financial backing from Binney and Smith, Incorporated.[6]

In November 1926 W. C. Hardesty Company began operations at a Carnegie, Pennsylvania plant. “The first products made were stearic acid, Oleic acid, crude glycerin, stearin pitch, and animal and vegetable fatty acids.”[7] Innovation soon followed, and “disastrous fire” wrecked the plant in April 1929 “… before most of these undertakings could be translated to full-scale production.”[8]

Disaster from volatile glycerin would in due time rain from skies at unfathomable scale. On 6 August 1930, in early stages of Great Depression, William, Mary E. and ‘Lavina’ Hardesty returned to New York from Bremen in seven-day crossing. Aboard newly refitted North German Lloyd luxury liner S.S. Columbus (left). W. C. Hardesty Company bought Century Stearic Acid Candle Works, Inc., at Manhattan, in December. Operating as a wholly owned subsidiary, operations were relocated to Dover in 1933. Where sons of Thomas Hardesty (1820-1869) depicted in 2019 post had launched from flour milling at scale into banking … and one of them, Alonzo Haines Hardesty (1846-1892), had fathered Walter Collins Hardesty. Having relocated to spectacular manse in Daytona Beach, Florida environs a decade earlier, Walter was beckoning clientele nationally to his glamorous ‘Riviera on the Halifax’ resort in 1933. And struggling with launch of million-dollar development for extravagant Rio Vista community. He had no Dover overlap with our subject. [UPDATE: Practicalities of Idealism, Chapter One introduces Walter Collins Hardesty, Sr.]William Hardesty’s processes diversified between industrial supply and consumer goods including cosmetics and crayons. “Also in 1933 a new plant was established at Los Angeles, the first fatty acid plant on the West Coast,” reported Haynes.[9] “The original quarters being outgrown by 1937, a larger building was erected.” 17 February 1937 reporting in Daily News at Los Angeles described “Explosive force released by atomic action of hydrogenated oil caused a blast …” and estimated $10,000 damage to W. C. Hardesty plant at the harbor. His initiatives suffered second industrial catastrophe in eight years.

“I am W. C. Hardesty of W. C. Hardesty Co., Inc. And business is good! We have done more business in the first two weeks of January than we did the whole month of December.” Henry Morgenthau, Jr. (1891-1967) was Secretary of the U.S. Treasury when taking 2 February 1938 meeting with a cadre congealed as “Association of Small Business Men of the Second Federal Reserve District.” One gets a sense of Hardesty’s gregarious personality from the Secretary’s diary: “People who order from us, like Firestone Tire and Rubber Co., when they send their orders in, want them shipped the same day. Wonderful!”

Hardesty gave backstory in his own words. “We entered business in 1926. We go overboard, hook line and sinker for everything we had, when we go through the depression of 1931-1932. Then we get our friends to come to our rescue with $150,000” as bonds to be repaid over ten years. By New York Times reporting on “Small Business Parley,” Hardesty advocated U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation resume lending from $1,500,000,000 fund. I assume ‘friends’ to have been bankers. They may have been corporate co-investors.

Hardesty presented as attuned to manufacturing processes and business accounting. He detailed specific machinery purchased with borrowed money in 1935, “… and we paid taxes of $11,371.19. In 1936, still with the spirit of enthusiasm, we spent [an apparently borrowed] $31,705.09 and, glad to say, we paid $25,207.53 in taxes.” In back-and-forth with Morgenthau he declared 11% corporate profit on $1,800,000 gross business.

While angling for clarity on government policy, the forty-six-year old conveyed a certain folksiness, referring to Washington, D.C. “fellows up there who are now giving us the ha-ha.” Hardesty gushed “I am one of the fellows who thinks the Government has done a swell job. I want to congratulate the Government and the wonderful spirit which is going along.” “Let me say, from my angle, my treatment from the banks was fair, from the Manufacturers Trust, from the National City, from the Sterling Bank; all right. We are getting a very moderate rate.” “… so far as I am personally concerned, I have no complaint.”

Transcript ran twelve pages. A dozen Association men attended; Hardesty occupied Morgenthau for the final two pages. And prevailed. Obtained promise of immediate meeting with the President’s Special Tax Advisor, Undersecretary Roswell Magill (1895-1963, with Morgenthau, left). Hardesty Company operations in 1938 unfurled further with $50,000 investment in Toronto, Canada subsidiary and W. C. was on trajectory to sincere financial comfort. As top-echelon industrialist. Or ‘Small Business Man.’

William was not an absentee Dover Business Man. Daughter Elizabeth was Stenographer at W. C. Hardesty Company there, and by 1939 married Walter W. Somers (1909-1993) … Superintendent of Hardesty’s Dover operations.[10] Somers appeared at Hardesty’s side in 27 March 1939 reporting (right) on act I find particularly commendable. Under our folksy subject’s leadership, his company responded to capitalism’s decade of job eradication and wage suppression. Increasing for a second time compensation paid Dover’s two hundred or so employees. Dispersal of additional $1,500 in bonuses transpired as unilateral act, President Hardesty failing to obtain industry-wide consensus for such.[11]

Defendant W. C. Hardesty Company, Inc. – described as “a corporation of Delaware doing business at Dover, Ohio” – prevailed in patent infringement case brought by New Process Fat Refining Corp. Decided 16 November 1939, defendant’s means of steam-distilling fatty acids did not incur royalty. Important for this narrative, ruling found “Raw fatty acids are derived from garbage, grease, tallow or cottonseed foots. This raw acid is a chemical composition of [industrial] fatty acids and glycerine.”[12]

Society pages noticed W. C. and Mary Hardesty spent Christmas of 1939 at the posh El Mirador Hotel, Palm Springs, California. Star-studded New Year’s Eve parties there had become a rage in elite social strata. Our subject reported 1939 earnings exceeded $5,000.

1940 census entry from Greenway Apartments residence he shared with Mary at Forest Hills, Queens, New York seemed underwhelming: Hardesty’s occupation was enumerated succinctly as Executive at an Oil Company. (W. C. Hardesty Company that year registered a trademark.)

Poignantly, “With W. C. Hardesty of New York City, president of the Dover W. C. Hardesty plant, attending [Grace Lutheran Church celebration of the 4th of July, 1941 at Dover] for the baptism of his granddaughter, Elizabeth Louise Somers,” (1942-1998, left) our subject matched congregational funding in purchase of a $25 war bond. William’s well-bred daughter ‘Viv’ that summer (at Forest Hills) married commercial artist Joseph William Shaw (1913-1982).[13]He provided W. C. Hardesty Company corporate headquarters on 42nd Street, in the heart of Manhattan, as means of contact. National Academy of Sciences inventory for available research facilities described five chemists then at W. C. Hardesty Company’s Dover plant. (At least two, when later lauded, cited time spent in these laboratories.) It was the only facility in the nation found producing sebacic acid. His firm complemented a mere five others in production of fatty acids. Dover output “helped to furnish glycerin used in the napalm bombs which burned the enemy out of Pacific Island pillboxes,” reported Daily Times from nearby New Philadelphia, Ohio. “High-altitude bombers carried Capryl alcohol to keep hydraulic systems working at extreme temperatures. Even a special lubricant was made for General Eisenhower’s forces and flown to them in time for the invasion of France.”

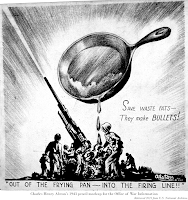

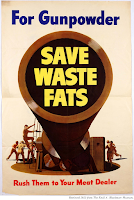

U.S. Department of Agriculture ‘Food for Freedom’ instruction sheet brandished (elements, right) strategic partnership. Behind fat globules’ marching ranks stood ‘Glycerine Refinery.’ A contrastingly sober Kitchen Grease Quiz circulated in 1942. Version distributed by Oregon State Salvage Board to local committees addressed housewives as intelligent actors in war effort. Disguised fact sheet detailed curtailment of vegetable oil supply in global terms, addressed protections against potential kitchen grease diversion to profiteers. It gave 12% as effective rate for glycerin refined from household fats.[15] Seven pages of suggestive messaging concluded with proposed supportive slogans … none as catchy as “Loose lips sink ships.” Pluto and Minnie Mouse got in the act in the summer of ’42. “Every skillet is a little munitions factory,” voice talent Arthur Gilmore (1912-2010) pitched during high-quality Walt Disney Production of Out of the Frying Pan into the Firing Line. 3-minute Technicolor animation promoted recognition of ‘Bring Waste Fats Here’ … in-store insignia (left) prepared by Glycerine Producers and Associated Industries. American entry into global conflict inflated Hardesty’s already considerable enterprises. Per Haynes, “These expanded production facilities were of incalculable importance to the splendid production records achieved by West Coast fatty acid-consuming industries during World War II.” Help Wanted ads sprouted in the Los Angeles Times in January 1943 ... offering “Chemical Plant Work, Experience Not Necessary.” Openly stated wage offer was unique among competitors for labor. Within weeks, dense, six-line ads were replaced by two-inch vertical swaths (right), to which “Essential War Work” was added. By April the firm specifically targeted Negro laborers, offering the same starting wage. Which escalated to 93¢-$1.08 in June. The Company pledged to retain Engineers following war’s conclusion. National quotas for scrap drives were set in 1943. Officials purposefully expected collection of 200,000,000 pounds of household fats. Bulletin went out 10 May. Under ‘Los Angeles War Council,’ a War Production Board heralded “all-out national effort to put 17,000,000 pounds a month of waste household fats into war production -- the makings of 8,500,000 pounds of dynamite for our fighting men.”[16] It also proclaimed the American Meat Institute would implement the campaign “through every meat dealer in the United States.” U.S. Citizens Salvage Committees in Southern California organized under slogan “A Spoonful of Grease a Day will Blow the Axis Powers Away.”

Operation Gomorrah, or the ‘Hiroshima of Germany,’ resulted in nearly 40,000 civilian casualties following massive-scale Allied firebombing raids on Hamburg at end of July 1943.

Time would elapse before the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) expanded messaging beyond result in explosives and incendiaries. Lubricants, also within W. C. Hardesty Company production capacity, joined military medicines and protective coatings as rationale in ongoing pleadings for salvage fats.

Graphic posters, intended for butchers’ shops, captured my imagination. Walter DuBois Richards (1907-2006) was already a prominent Printmaker, Painter and Illustrator when producing 1943 signboard while assigned to OWI. I found his treatment of gun emplacement (right) downright painterly.[17] Intensely provocative ‘Save waste fats for explosives’ (left) was work product of Henry Koerner … named Heinrich Sieghart Körner (1915-1991) at Austrian birth. He would accrue multiple awards for his postwar art.[18] One can sense by 1943 illustration ‘Kill These Rats’ (right) Alfred John Plastino (1921-2013) had already moved from Marvel Mystery Comics and then departed Novelty Comics for military service as Illustrator. His representation of Superman in particular would appear in comic books and syndicated comic strips long after his war service.

Richard Hardisty, father to our subject, died 22 December 1943 at his Mitchellville, Maryland farmhouse. Services were held Christmas Eve and, age 79, he was interred as his parents had been. At Holy Trinity Church cemetery.

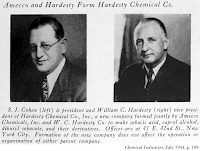

“Extensive research and the resultant development of HARDESTY fatty acids during the past few years have brought forth qualities and high purities not heretofore obtainable — fatty acids that are extremely light in color, free of contaminants, and each with unusual characteristics to meet the buyers' specifications,” advertised W. C. Hardesty Company in May 1944. Dover factory appeared first in list of operations run from Manhattan offices. (I leave it to readers to assess whether our subject posed (left) as left-most decision maker for full-page ad. The model was certainly Rooseveltian.)

Crowley found “Hardesty was having difficulty in getting into production” at a recently retired war production plant, Henderson, Nevada. Amecco Chemicals, Inc., underwriters for Hardesty Chemical Company, by 1948 undertook financial obligations and I suspect Hardesty had sold his stake in it. (See endnote.) William and Mary Hardesty in the Spring of 1948 flew from Nassau, Bahamas to Miami, Florida in what was obviously leg in wider ambulation. Our subject won Senior’s Championship when in golfing pair at Winged Foot course, Mamaroneck, New York that summer.

William Hardesty was not at Dover for deadly 1949 explosion depicted in my 2019 post. (The imaginative Walter Collins Hardesty, Sr. was dead, as was his same-named son. Walter Collins Hardesty III (1938-1984) was age ten … and likely in his mother’s Daytona Beach household.) It may be of slightest interest that Daily Reporter at Dover placed Hardesty Milling Company among ten largest companies there in 1929. (It was then under Presidency of paternal first cousin to Walter Collins Hardesty.) In list compiled recent to 1965, “Harchem Division of Wallace & Tiernan” sat in top tier of principal Dover companies. Our W. C. Hardesty had introduced the manufactory to a disused plant there.

Samuel Harold ‘Sam’ Bonifant (b. 1908) died of burns in 1949 pandemonium. Twenty were injured in all. “We want our appreciation expressed to Mr. Hardesty and other officials,” President of Local No. 20, International Chemical Workers Union, told the press in August. Each employee had been awarded $50 bonus ... as “token of the company’s appreciation of the fine spirit and loyalty” shown following disaster. (Each check included note from Hardesty.) Widow and mother of two, Edith Isabell (Besozzi) Bonifant (1908-1976), was compensated almost $30,000. Company outlay formed nearly half of her quittance. None had been laid off when Somers announced weeks of paid vacation in July dependent on length of employment.

Somers was summarily replaced as Plant Superintendent. Though I don't know at whose instigation, Binney and

Smith assumed management of W. C. Hardesty Company in early 1950 ... and they subsumed his corporate identities to Belleville, New Jersey base of operations. (Dover’s

local baseball team played as ‘W. C. Hardesty’ into the mid-1950s … several seasons after

Wallace & Tiernan acquisition of Dover plant.)

Somers was summarily replaced as Plant Superintendent. Though I don't know at whose instigation, Binney and

Smith assumed management of W. C. Hardesty Company in early 1950 ... and they subsumed his corporate identities to Belleville, New Jersey base of operations. (Dover’s

local baseball team played as ‘W. C. Hardesty’ into the mid-1950s … several seasons after

Wallace & Tiernan acquisition of Dover plant.)

William was described as ‘Executive, Manufacturer of Raw Materials,’ working 40 hours a week, in April 1950 census. He and wife Mary were ensconced in stately Larchmont Village home, Westchester County. ‘$10,000+’ (overstricken) appears in columns both for earnings and income aside from it (dividends in first instance, perhaps proceeds from buyout in the second).[19]

The following year, Hardesty (placed third in his age class for U.S. Senior’s Golf Championship and) established entities with corporate relationships that had apparently been distilling since wartime. Hardesty Industries Company was established in joint venture with Philadelphia tannery under new generation of management by Jacob Stern & Sons.[20] Hardesty was also credited as founder of the Acme-Hardesty Company: it remains a branded division within Jacob Stern & Sons to this day.[21]

He was declared survived by widow Mary, his daughters Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Bailey and Vivian (as Mrs. Frank Foster, Jr.), two granddaughters, and sister Emma Gertrude (Hardisty) Barker (1895-1987). To put our subject’s trajectory into perspective, Gertrude had by 1950 divorced John Anderson Barker (1885-1956) … who was in 1940 enumerated as Stationary Engineer at a Baltimore scrap yard.[22]

~

The author has been a collector of World War I propaganda art.[2] William C., age eight, was in 1900 enumerated in Richard Hardisty’s rented Baltimore domicile. (Consult endnote [22] for disambiguation attempt.) Three of six children born to Mary Emma (Murr) Hardisty (b. 1863) survived … William and sisters ages six and four were enumerated. The quintet occupied a different Baltimore household in 1910; two ironworkers boarded with them. Our subject may have left home as a teen: a William Hardesty appeared in 1910 Philadelphia directory as Bookkeeper.

I note some decline in intergenerational status. Baltimore Sun obituary for Richard Hardisty, Sr. (1829-1908) credited William’s paternal grandfather as progressive Farmer, General Store Merchant at Collington (now subsumed into Bowie), Maryland. As “intimate social and political friend” of one-time Governor Oden Bowie (1826-1894). Richard, Sr. likely married Margaret Talbot in 1862 and was taxed four years later for carriage, piano and gold watch. (Her father, Thomas Jefferson Talbot (1804-1869), was well-situated at 800-acre ‘Medford’ estate, Prince George’s County, Maryland.) Richard, Jr. was first-born, preceding at least nine siblings.Census records for 1915 and 1920 suggest Richard, Jr. was at Manhattan. As ‘Farmer’ on East 81st Street; then as Manager of a Club. If so, Richard, second wife and Dressmaker Sarah T. McGrail (1875-1968), with her three sons, four daughters (and, initially, her mother and sister, also in Hardisty household) would have preceded his son William to New York. Richard Hardisty was enumerated 1930 as Tobacco Farmer, Prince George’s County … with (no wife) daughter Emily (1919-2017) born at New York, and that McGrail sister-in-law, in his domestic arrangement. Emily's obituary divulged mother Sarah remained at New York. BACK

[3] Our subject elevated from Sales into corporate machinations of impressive scale: “The General Manufacturing Company has purchased from W. C. Hardesty for a nominal consideration the lot on the north side of Delaware avenue in the middle of Bigler street. The ground was purchased earlier in the day by Mr. Hardesty … for $110,000,” reported The Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 July 1918. G.M.C. expected to erect a number of factory buildings at 204-acre parcel.

See The American Fertilizer Handbook, Vol. 8 (1915), p. A-67: W. C. Hardesty appeared as Treasurer for Martin Fertilizer, Inc. at Norfolk, Virginia (with plants at Baltimore and Philadelphia). Hardesty would have been, at most, age 24. See Moody’s 1920 Manual, p. 1055: W. C. Hardesty was listed as a Director of D. B. Martin Company, Philadelphia slaughterers also manufacturing fertilizer, glue, soaps and broad range of meat-based products. The company was valued at nearly $10,000,000. BACK

[4] Unidentified brother, sketched into 1917 draft record almost as afterthought, was perhaps son to his father’s second wife. He may have been brother to wife Elizabeth Heck. She had been only child in Henry Granville Heck (1870-1918) household at Dauphin County, Pennsylvania 1900. Village of Heckton had been established there 1832 by Dr. Ludwick ‘Lewis’ Heck (1810-1890). Grandsons born at Heckton achieved distinction. Among them, Lewis Heck (1889-1964), age peer of Elizabeth’s, was U.S. High Commissioner to Turkey 1918-1919. His brother Nicholas Hunter Heck (1882-1953) at time of Elizabeth’s marriage was pioneering underwater acoustics: he would revolutionize hydrographic surveillance. BACK

[5] Baby Ella Marie was borne from funeral service in Hardestys’ home in White Plush Casket (see right) by white hearse, to Laurel Hill Cemetery.Binney and Smith had profited immensely from carbon black (cast off by coal refining) and industrial coloring. They had introduced Crayola brand wax crayons in 1903. Principal’s wife Alice (Stead) Binney (1866-1960) is credited for combining French word for chalk, ‘craie,’ with Latin ‘olea.’ (Think olive oil.) Hardesty would make the most of oils, fats and Binney and Smith funding. Blackening formerly white Goodrich tires was apparently joint enterprise the companies performed. BACK

[7] Additionally, 1927 Buyer’s Directory gave Hardesty Company as source for Candle Tar and Distilled Red Oil. Adhesive Candle Tar was newly being processed via vulcanization for elastic properties. The latter was an oleic acid of distilled grease the texture of lard, preferred by textile manufacturers as a soap. Industry was beginning to explore Red Oil’s antiseptic and lubricating properties. BACK[8] See ‘Fire Loss Set at Million in Grease Plant,’ The Pittsburgh Press, 15 April 1929, p. 19, col. 8: “W. C. Hardesty, president of the Hardesty company, estimated the damage in excess of $1,000,000.” Firefighters required a day to extinguish fire originating in “still house” and which soon fed from grease and oil tanks. At least a hundred working men lost jobs. Same-day New York Times reporting described thirty buildings destroyed, $500,000 loss. Pennsylvania Railroad passenger traffic was shunted to branch route “because of the danger of tanks adjoining the right of way exploding.” Another account put Binney and Smith as facility owners, in the business of making pencils. BACK

[9] W. C. Hardesty Co., Inc. registered trademark HYDREX (right) in 1934. From description of goods and services: “Preparation of fatty acid of marine, animal, and vegetable origin for use as a rubber compounding ingredient, as an aid in the dispersion of pigments, as a binder in the preparation of buffing compounds, and as an ingredient in the compounding of lubricating greases.” BACK

[10] Wide-eyed “Plant Manager Walter Somers (pointing)” appeared (right) in 1949 Dover reporting beneath ‘Hardesty Plant Damage Over $275,000.’ Somers (who had no middle name; Draft Registrar noted middle initial ‘W.’ did not refer to any) had been “head of the GOP committee” inviting (U.S. Senator for Ohio and) Presidential candidate Robert Alphonso Taft, Sr. (1889-1953) to Dover in 1948 campaign to counter economic New Deal before an audience of five hundred. BACK

[11] Retrospect reporting recalled 55 Dover employees striking 4 August 1937 and obtaining wage increases. 1939 act was apparently unbargained follow-on. American Federation of Labor members nevertheless struck W. C. Hardesty Company in 1941. 8¢/hour pay rise had been bargained, unionists agitated for a closed shop and more favorable means of dues collection. BACK

[12] Cottonseed oil foots – or soapstocks – become admixtures of soap, vegetable oil and other aqueous liquids when refined from crude cottonseed oils. Our subject would in 1942 be named to ‘Soap and Glycerine Committee,’ by the U.S. War Production Board. W. C. Hardesty Company surfactant process would be referenced seventy years later, in another’s 2009 patent application. BACK

[13] After being elected President, freshman class at Linden Hall – Lititz, Pennsylvania boarding school (1929) – ‘Viv’ (right) had in 1937 graduated Penn Hall Girls’ Preparatory School at Philadelphia. The groom was of Vesper George School of Art at Boston. Connecticut death index would describe Joseph W. Shaw as President of Shaw Advertising. And widower to a second wife. BACK[14] mp3 audio file retrieved 20 May 2023 from sample shared at Old Time Radio Catalog, website OTRCAT.com. BACK

[15] Fat Salvage Program Copy Policy by the War Food Administration, February 1945, offered intriguing insight for using language to solicit intended behavior. Specified word choice preferences for instructing civilian participation. It opened with declaration defending “Need for salvaging used kitchen fats in 1945 is more important than ever.” Compare this with Strasser’s 2014 claims: “Women who did contribute felt good about being part of the war effort, even if that contribution was somewhat of a ruse. The types of explosives made with such fats were not of major importance in the war…” And “Keeping women busy and productive was the important thing.” See Turning Bacon Into Bombs by Adee Braun (2014).

For those interested in psychology of marketing messages to consumers, see A Turtle’s Approach to Truth (2023). BACK

[16] Independent Commodity Intelligence Services reported the American Fats Salvage Committee collected more than 924,000,000 pounds of household fat during their campaign. BACK

[17] Richards, probably at Manhattan by 1943, was 1936 graduate of Cleveland School of Art, less than 80 miles due north of Dover. I recommend the blog ‘Walter DuBois Richards,’ respectful and intelligent tribute by the artist’s grandson, Andrew T. Richards.

Copy for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History exhibit ‘Posters on the American Home Front (1941-45)’ described “Two contending groups within OWI clashed over poster design. Those who saw posters as “war art” favored stylized images and symbolism, while recruits from the world of advertising wanted posters to be more like ads.” We might deduce from Fat Salvage Program Copy Policy [at 15] that “Advertising specialists in OWI finally gained the upper hand in 1943.” BACK

[18] Koerner’s WWII poster ‘Someone Talked’ won award at National War Poster Competition by the Museum of Modern Art. He returned to Vienna in 1946: to discover his parents and brother – all but two of his relatives – had been deported and put to death during the war. BACK

[19] The Hardestys sold their five-bedroom Larchmont home … with “vapor oil” heating system and maid’s quarters (right) in 1952. To take up Sprain Road residence at nearby Greenburgh on Hudson River. Mary, active in Greenville Garden Club, entertained persistently here and at Sprain Road. BACK

[20] The Family History at Jacob Stern & Sons, Inc. website contends “A chemical engineer named William Hardesty approached Lucien Katzenberg [in hides and tallow business] with the proposition of splitting tallow to yield glycerine, a substance that could be used to produce explosives. The idea was appealing to the family and the plant was commissioned …” Hardesty was not known to have had formal science training. Acme-Hardesty celebrated 80th anniversary in 2023 with 49-page booklet. Jacob Stern & Sons’ single shareholder, Chairman Philip Lucien Bernstein (b. 1942) recalled meeting ‘Bill’ Hardesty, “... future co-founder of Acme-Hardesty, “a number of times” when a “youngster.” Per Bernstein, Hardesty “figured out” how brokers between fat renderers and soap industry could profit as manufacturers. “[His] proposition to my grandfather was that we take the tallow that Jacob Stern had access to, and split it to get the the glycerine, to sell to people who were making ammunition and munitions ... Hardesty was a chemical engineer by training and reckoned that there was a fortune to be made by selling material to the government to support the war effort.” As the U.S. began warring in Korea. “Glycerine, at the time, was worth close to a dollar a pound. The splitting idea had appeal and, before long, open kettles were added” to Jacob Stern & Sons facilities at Philadelphia. On incorrect premise, Bernstein reported “Hardesty went on to start another fatty acid business in Dover, Ohio. To this day, that plant still exists, in a greatly transformed state …”

Lionel® scale model train “tank cars lettered for Jacob Stern, the parent company of Acme-Hardesty, a firm in Philadelphia … were promotional items that Jacob Stern gave to customers as gifts or incentives around 1949 or 1950.” Asserting “no critical problems of fire protection are created,” 1963 Soap & Detergent Association report on fatty acid transport also described “specially lined cars equipped with heating coils …” to prevent discoloration. BACK

[21] “Acme Hardesty Co., New York, N.Y. Principally for hand soaps and resins” was listed behind only General Mills as members of Fatty Acids Division of the Association of American Soap & Glycerine Producers, Inc.” in 1953 Soybean Digest ranking (here). “Few products have a wider range of usage yet are more unheralded. The consumers of the end products never hear of fatty acids,” observed Pellett, who drew attention to “big expansion” in previous five years. Soybean fatty acids had been considered near-worthless byproducts of soybean oil refiner’s ‘foots kettle,’ sold only to soap manufacturers, who bought them for little more than transportation costs. “Now they are convertible into fatty acids of uniform grades which enter into products as various as rubber and paints, perfumes and paper, and insecticides and cosmetics. And fatty acids are quoted on commodity exchanges at about the price of crude soybean oil.” BACK

[22] 1910 census enumerated Richard C. Hardisty in first marriage, wife Mary E. in her second. And that three of six children born to her survived. William C. and Emma G. (Gertude) were recorded … as was daughter Ella M. (b. c1894). The quintet mirrored 1900 household. 1936 Baltimore Sun obituary cast Emma M. Murr (c1864-1936) as having married Richard C. Hardesty. 1937 Social Security application for Ella Matilda (Hardesty) Delker (b. 1893) gave Hardesty and Murr as parents. ‘Mary E.’ (b. c1862) appeared in 1870 enumeration for Baltimore household of William F. and Mary Murr. ‘Emma’ (b. c1862) appeared in enumeration of William and A. Mary Murr at Baltimore a decade later.

Vivian’s son Stephen J. Shaw (b. 1945) was not mentioned in maternal grandfather’s obituary. Viv made consequential second marriage … to Frank Brisbin Foster, Jr. at Manhattan in 1953. Significant heir to fortune accrued from Diamond Glass Company at Royersford, Pennsylvania, Foster also entered second marriage. He and Vivian returned in First Class Andrea Doria cabins from Naples in 1955. When Mary (Pierson) Hardesty removed to Haverford, it was to be near step-daughter Vivian. BACK

Ancestry.com subscribers will find sandbox titled ‘With the Spirit of Enthusiasm.’