Squire Turner was adamantly pro-slavery. Hewing to the nation's founding compact, Turner was a property-rights man. Though the actual wording should be attributed to someone else, Turner would no doubt agree with a report made after the 1850 Constitution massaged Kentucky's legal relationship with slavery: Turner is often credited with 'enshrining the rights to property (slaves) as higher than divine law.'

I recently found this link to a Kentucky Gazette report of a Turner voting in the Kentucky House in 1819. It was not 'my' Squire Turner, but his uncle (and mine) Cornelius Turner (1770-1835), from Warren County, Kentucky, who served from 1816-1820 before being elected to the Kentucky Senate. The Gazette reported that - after the state senate deadlocked - Cornelius Turner voted in the Kentucky House to send Col. Richard Mentor Johnson (c1780-1850) to the U.S. Senate.

Ever heard of Richard Mentor Johnson?

He was already nationally renowned in 1819, having been credited with killing Shawnee Chief Tecumseh (1768-1813) at the Battle of the Thames, during the War of 1812. His 1819 appointment to the U.S. Senate was a stepping stone: in 1837 the Senate elected Johnson to be the ninth Vice-President of the United States. Johnson played a nominal part in Martin Van Buren's first administration.

It seems Johnson, like Squire Turner, has not fared well in remaining current in historical chronicles. Both were popular men later judged ignominious. Both held views on race that were considered disturbing. Both were slaveholders ... yet Johnson held his slaves perhaps more closely.

By the time of his appointment to the U.S. Senate, Johnson had fathered two daughters by Julia Chinn (1780-1833). Sometime after his father died (1815) Johnson had inherited Chinn from his father's estate.

From Wikipedia:

"As his prominence grew, [Johnson's] interracial relationship with Julia Chinn, an octoroon slave, was more widely criticized. It worked against his political ambitions. Unlike other upper class leaders who had African American mistresses but never mentioned them, Johnson openly treated Chinn as his common law wife. He acknowledged their two daughters as his children, giving them his surname, much to the consternation of some of his constituents."Johnson gave his daughters more than just his surname. He gave them land. His 1834 biography (propaganda including lyrics to a drinking song designed to popularize the 'gallant patriot's' bid for the Vice-Presidency) makes no mention of Julia, or daughters Imogene Malvina and Adaline Chinn Johnson. A wedding announcement in the Lexington Observer and Kentucky Reporter (based in Fayette County) addressed the sensitive issue after Adaline married Thomas W. Scott in 1832:

"This is the second time that the moral feelings ... of the people of Scott County have been shocked and outraged by the marriage of a mulatto daughter of Col. Johnson to a white man, if a man, who will so far degrade himself; who will make himself an object of scorn and detestation to every person that has the least regard for decency, for a little property; can be considered a white man."

"How long will the people of Scott County - of Kentucky - permit such palpable violations of the laws of their state to be committed with impunity? How long will the moral and religious part of the community suffer such an indecent and shocking example to be set for their sons and the rising generation, before they put their veto upon them? Before they consign to private life at least, if not to infamy, those who encourage such violations of the laws both of God and of man? The laws of Kentucky forbid, under heavy penalties, a white man's marrying a negro or mulatto, or living with one in the character of man and wife."In 2007, David Mills, writing in the Huffington Post, made some contemporary observations about Richard Mentor Johnson's position in family trees. It seems that many who descend from the nation's ninth Vice- President are unaware of their relationship to him: intervening generations of storytellers - wanting not to claim their descendancy from a woman of color - simply relinquished their claims upon a war hero and semi-successful political aspirant. (Time once voted Johnson the nation's forth-worst Vice-President in history.)

It's admittedly complicated, but their are reasons to admire Julia Chinn. An assumed descendant declared Johnson's captive chattel "an excellent Châtelaine for his home," as she is known to have wined and dined the aristocratic French revolutionary, the Marquis de Lafayette, when he visited the plantation in 1825. Chinn managed Johnson's business affairs during his absences in the nation's capital. Dedicated genealogists might be put off by the fact that, as miscegenation was then illegal, documentary proof of the marriage becomes problematic. Others may be put off by the fact that Chinn exercised a master's rights over slaves in her role as Johnson's plantation manager. Indeed, Johnson gave slaves as part of his daughters' dowries.

Admiration for Richard Mentor Johnson comes in a mixed bag as well. He educated his daughters, provided them with superior social graces and economic advantages. Mills declares them "bona-fide, fully vested white people." However, according to Johnson's official Senate biography:

"When Lewis Tappan asked the vice-president to present an abolition petition to the Senate, Johnson, who owned several slaves, averred that "considerations of a moral and political, as well as of a constitutional nature" prevented him from presenting "petitions of a character evidently hostile to the union, and destructive of the principles on which it is founded.""More extraordinary, following his wife's death in 1833, Wikipedia reports Johnson began a relationship with another family slave. When she left him for another man, Johnson had her captured and sold at auction. He then began a relationship with her sister.

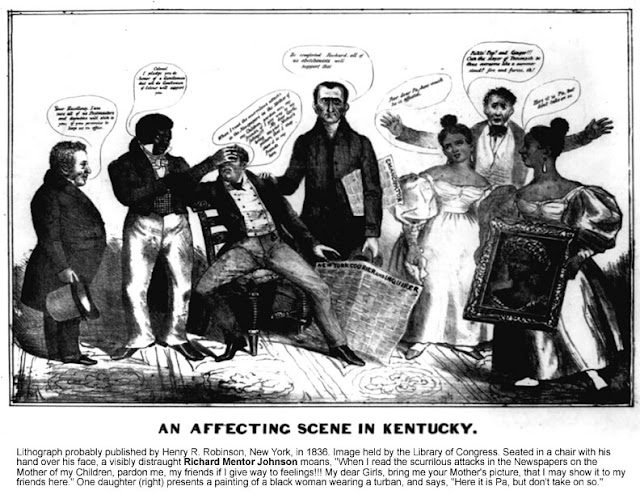

Johnson paid a political price for bearing an interracial family. New York papers ridiculed Johnson's domestic situation, and the Democrats' constituency as well.

|

| A racist attack on Democratic Vice-Presidential candidate Richard M. Johnson. |

Johnson's lifestyle choices also bring into relief a side of Abraham Lincoln you may not be aware of. According to Clifton Porter II, blogging as Undercover Black Man, 'Honest Abe' exploited Johnson’s relationship with Chinn, to score points against Stephen Douglas during the legendary Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858."Lincoln asserted, to the applause of his audience, that “I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races… nor qualifying [Negroes] to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people…”"Porter reports Lincoln saying:

"I do not understand that, because I do not want a negro woman for a slave, I must necessarily want her for a wife. [Cheers and laughter.] My understanding is that I can just let her alone. I am now in my fiftieth year, and I certainly never have had a black woman for either a slave or a wife …Johnson had died eight years earlier, months after Kentucky's new state constitution went into effect. One provision in the 1850 constitution provided that "no slave shall be emancipated but upon condition that such emancipated slave be sent out of the state." [See page 137.]

I will add to this that I have never seen to my knowledge a man, woman or child who was in favor of producing a perfect equality - social and political - between negroes and white men. I recollect but one distinguished instance that I ever heard of so frequently as to be entirely satisfied of its correctness – and that is the case of Judge Douglas’ old friend Col. Richard M. Johnson." [Laughter.]

Johnson's daughter Adaline had died in 1836. Among first-degree family, only daughter Imogene survived Kentucky's gallant patriot. Although Johnson willed vast property to his daughter, Imogene was prevented from inheriting her father's estate: the Fayette County Court considered her illegitimate and without rights. Upon Johnson's death, the court ruled that "he left no widow, children, father, or mother living."

Julia Chinn is depicted as an octoroon, or 1/8 black (i.e., she had one black great-grandparent). If so, Johnson's grandchildren - also deemed ineligible for their inheritance - would have been 1/32 black. To connect those grandchildren to a black ancestor is to travel as far back in a family tree as I must go, to claim relationship to my 2nd great-grandfather, James Berry Turner (1820-1867), half-brother to the above Squire. While that relationship seems a long road into a distant past, and while white supremacists were willing to reach that far back to besmirch Julia Chinn and Richard Mentor Johnson, it is the same distance I must travel from the 21st century, to claim relationship to James Berry Turner, who - contrary to his half brother's agenda - sought to nominate emancipationists to Kentucky's 1849 constitutional convention.