UPDATE: Click Finding Everett to see ancestry.com tree.

Divorce. My bluegrass, Kentucky-born maternal grandmother whispered the term in adult company in much the same way she confidentially breathed "cancer." Taboo firmly censured marital disunion in her parents' line. When a television commentator recently used the term 'scandalous,' in reference to the practice in the 1920s, the disapprobation resonated with me. I agreed with the contention.Another penchant drives this post. I seem not at all deterred from researching subjects who leave no survivors. I'm impelled by source documents: if it emerges in my awareness, I don't mind compiling a distinguishing fact into the arc of a family member's life … though few will ever trace its contours.

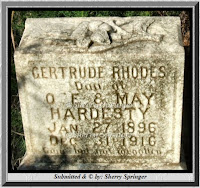

Gertrude died pitifully young.

Her final year was likely one of considerable suffering. On 11 May 1916, the 20-year-old gave birth to daughter Gail. The child died four months later, on 12 September.

Gertrude did not divorce. Those who survived her did provide ample opportunity to discern whether the practice was indeed scandalous.

|

| Oklahoma Cemeteries Website, ©Sherry Springer. |

My Great Aunt's potential line of descent terminated 31 December 1916. A niece, not yet born when Gertrude died, ascribed demise to tuberculosis. One must be suspicious regarding cause of death in all who pass on New Year's Eve. Gertrude and Gail share an untended Fallis, Oklahoma grave with an interloping, scrub cedar. Their stone is inscribed Gone but not forgotten" … in an overlooked burgh now portrayed by the state's tourism department as a ghost town. (Note that grave marker above references parents 'O. E.' and May Hardesty … not Gertrude's spouse.)

|

| Images enlarge when clicked. |

I'd been asked about Gertrude when posting a schoolhouse photo (bottom) to a Facebook group last week. I knew precious little about her spouse: his name was relayed to me as Everett Rhodes. He was a 'railroad man.' I was given to think the groom held an itinerant job, and – adding to Gertrude's sorrowfulness – may not have been present throughout her final year. Mr. Rhodes quickly moved on, while my grandfather's family remained with localized grief during the misery-inducing Dust Bowl.

Thinking to check my facts, I dug into the record. I sifted through ancestral photos and my document cache; I wandered among family-depicting databases. One online community can be particularly helpful: Find A Grave is a self-organizing group of genealogy 'angels.' Most often altruistically motivated to document 'what is,' they photograph grave markers and manage online profiles. (Some admittedly embellish profiles, introducing facts not in evidence.) While the data set may not be verifiably true, at least it's carved in stone. [UPDATE: for-profit genealogical giant ancestry.com, owned by private equity firm The Blackstone Group, bought Find A Grave in 2013.]

It was gratifying to discover Sharon Spain Ingle had created a Find A Grave memorial for Gertrude (Hardesty) Rhodes. It is hyperlinked to daughter Gail, perhaps the child's only original manifestation in the World Wide Web. I was touched to discover a Joyce Hopkins had in 2011 laid virtual flowers on each of the pair's memorial pages. I lovingly submitted hyperlinks to Gertrude's parents, as if somehow reuniting her.

Research then brought me to one of those supremely gratifying moments. A source document, excruciatingly pertinent to these admittedly minor characters, came to my attention: The Oklahoma Historical Society has posted the 2 July 1915 issue of the Carney Enterprise. Two sentences in the 12-page weekly leapt out: "It is reported here that Everet [sic] Rhodes and Miss Gertrude Hardesty were married at Fallis last Sunday. We have no particulars."

We have no particulars. That's an affront to a researcher. A wedding date of 27 June produced no trove among returns from Internet databases. Gertrude, married but a year and a half, remains a stub in the few online trees where the most diligent family historians deigned to record her birth ... likely as they discovered her enumerated in O. E. and May's 1910 census entry, when that family of five farmed Fallis environs in Lincoln County, Oklahoma. None depict spouse or child.

An Everett – born in Missouri, September 1894 – was, in the 1900 census, identified with parents 'Ed.' and Anna, and 2 Rhodes siblings ... in Lincoln County's Otoe Township. At age 16, Everett was no longer resident in the 1910 household of Edwin Beardsley Rhodes (1869-1939), then at Cimarron, Lincoln County. Rhodes the elder left farming, for work at a rail yard as Section Foreman. The younger Rhodes left school.

And thus begins a most delicate task.

I've pursued racial justice work that at times broaches difficult conversations about family heritage: I peer into Rhodes and ancillary family trees posted online, and I suspect a social minefield awaits ... as I consider inviting collaboration, in ascertaining whether Gertrude was the first wife of Ollie Everett Rhodes (1894-1980). Nearly all of this man's profiles reference a September 1894 birth date: no Rhodes researcher at ancestry.com offers a Hardesty spouse. Two camps have formed. Two spouses are generally assigned to Rhodes. (See the chart, next paragraph.) Only a couple profiles list both.Here's the rub. When ferreting out 'the particulars' of unsubstantiated family lore, I depend – in the main – on descendants who hold ancestors in some esteem. Else they might not devote the effort of compiling records and offering online trees. I suppose I could have approached each researcher with a limited fact set, foregoing mention of a marriage they may not be aware of. It may be completely self-defeating (and is certainly cumbersome) to drop intermarriage on them ... but, now that I have the fact sets, I feel somehow compelled to lay them out. Untangling this generation's web of relationships certainly inspired a learning experience for me. Divorce may not have been as scandalous at I've been led to believe: heck, it may not always have been prerequisite for re-marriage.

|

| Brick School, Fallis, OK, 2011 |

By the summer of 1917, months after Gertrude's death, widower 'Everet' was almost undoubtedly going by the name 'Ollie E. Rhodes.' He was a Telegraph Operator for the Denver & Rio Grande Railway Company ... at Grand Valley, Colorado. As the Roaring Twenties kicked in, he was with the Southern Pacific Rail Road at Casmalia, Santa Barbara County in California. He was barbering in Santa Margarita, San Luis Obispo County there, likely by 1922.

Rhodes launched into an odyssey with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway. As Telegrapher and Clerk, he thrashed about in Arizona and California until his 44th birthday ... in 1938.

I now introduce Loretta Magdalen McGeough (1896-1976). She and Rhodes married in 1960. Santa Barbara voter registration records have the pair sharing an address (she using the surname Rhodes) c1939, however. 1933 birth records of stillborn daughter Sarah bear the surname Rhodes, as did Mary Ann, born two years later. Delay in solemnizing this Rhodes partnership may result from unresolved, earlier unions: Loretta had been married before. Three times, by my count. Twice by Catholic clergy.

Loretta was, apparently, the first wife for all but Ollie.

An earthquake hit Santa Barbara the following June. It's unclear how much damage was done to inventory at Frederick's employers, Bailard-Cramer Piano & Phonograph Co. (left). One can surmise – likely for completely distinct reasons – that the couple's marriage took a shellacking in this period. Loretta moved on, Frederick escapes my ability to find him subsequently in any record. Perhaps the earthquake got him.

It's my belief that Frederick Orr doesn't even have a memorial at Find A Grave. He left no heirs I'm aware of. That too seems to be a limitation on representation in my online environment: few care sufficiently to request photographs of their graves.

Loretta's marriage the following year, to Vandal Martin Branstetter (1898-1988), reveals divorce to be far more common than I realized. Vandal left his widowed mother in Portland, Oregon to take up work as a Steam Shovel Operator in Santa Barbara. (Perhaps he warbled along with Al Jolson, en route.) Vandal and Loretta Orr, then of Los Angeles, married at Idaho Falls, Idaho in the autumn of 1926. Walter Bruley that year listed Loretta as his wife, in the Denver City Directory.

Vandal was back with his mother when, in 1930 and six weeks after Walter obtained a Denver divorce from Loretta E. [sic] Bruley, an Oregon court provided Vandal judicial separation from Loretta M. Branstetter. That's Loretta (McGeough, Bruley, Orr) Branstetter ... who would go on and marry Rhodes.

The following summer, in 1931, Vandal married fellow Portlander, Margaret Jolly Christie (1900-1962) at Skamania County, Washington. Except that her surname was Liston. A decade earlier, Margaret had married J. Delbert Liston (1894-1976). The Eugene, Oregon automobile salesman was enumerated as divorced in the 1930 census. By 1935, 'J. Del' was married to Junior High School Teacher Iva Belle Wood (1894-1947). Well, that was her maiden name: Iva had, in 1920, gone to Idaho to marry Charles Herman Brune (1900-1978). Charles in 1927 married Elizabeth Mills Harriman (1900-1974) ... also at Skamania, on the Columbia River and not far from the home place of your diligent family history contributor.

Elizabeth, thankfully, had not been married previously.

Iva (right), like Louise, Loretta, Walter, Frederick, Vandal, Margaret and J. Delbert, spent time as divorced persons in economic downturn of 1930. In Santa Barbara at the time, census takers might not have caught up with Ollie Everett Rhodes.

Vandal was, with his mother, settled and farming in Colorado by 1940. Second spouse Margaret, then a doctor's assistant, remained as a renter in Portland ... with 2 young daughters. Had he not succumbed at or near the U.S. Embassy in Costa Rica, Vandal might have a Find A Grave memorial. The most diligent among those who voluntarily inventory cemeteries could have clarified, via hyperlink, this relationship web.

Though she is buried in Portland, and he among an extensive Eugene family, childless couple Margaret and J. Delbert have memorials. And the divorced couple are hyperlinked (a diligent Find A Grave caretaker posted and sourced Margaret's Oregonian obit: it references Vandal). J. Del is not linked to second wife Iva, however. Iva shares a fate similar to Gertrude's: though her death certificate lists 'Iva W. Liston,' a grave marker in her parent's Wood plot reads 'daughter.' No surname at all is carved into it. Iva's Find A Grave memorial is not linked to anyone.

Elizabeth (Harriman) Brune bore Charles two sons. These parents are buried where they started a family while tending sheep. They are linked in a virtual, Wasco County, Oregon Odd Fellows Cemetery. Digital flowers also appear at these graves.

I'm not casting aspersions. This post is to be a digital beacon. To lure those with family lore describing this cast of characters ... to leave comments below (or here), should they be able to corroborate, debunk or clarify my contention: that Everett Rhodes was initially married to Gertrude Hardesty. "Do I have sufficient evidence," I wonder, "to suggest caretakers of Ollie E. Rhodes' Find A Grave memorial accept a link to Gertrude's? How much social unpleasantry would this create?" [UPDATE: subsequent to this blog post, genealogy angels knit Ollie to his purported three spouses.]

Conversational taboo preserves family dignity. It also allows those subsequently afflicted, by disease or societal choices, to be handicapped in isolating belief that they are the first in their family to ever experience a particular hardship. I try to avoid false pride; forgo taking unwarranted, psychic credit for ancestors' meritorious conduct when I find it. So too do I try to avoid shame. Particularly with regard to slave-owning ancestors. I admittedly find it generally challenging not to judge historical figures against contemporary mores.

When I am able to suspend judgment, I actually grow closer to 'what was.' It seems somehow more rewarding than allowing imagination to paint the past.

Those of you who delve concertedly into family history will understand my sense of immersion; of being neck-deep … cross-referencing documents as I'm retaining names and dates. While the image of the log schoolhouse (below) initiated this study, it was an extraordinary observation that prompted me to draft this post.

This photograph, of a rustic, one-room schoolhouse near Agra, Oklahoma, triggered my labyrinthine investigation. Gertrude is depicted with the letter C.

I find this final image (below) compelling, and wish it to be unleashed onto the World Wide Web. O. E. & May's children: Hallie Hardesty (1893-1980), Roy David Hardesty (1891-1970) and Gertrude Hardesty (1896-1916). Roy married a divorced woman whose own father declared himself 'widowed' in the 1920 census ... though his spouse lived on. Roy's son, my father, would divorce before establishing a family. I myself am twice divorced.

Iva (right), like Louise, Loretta, Walter, Frederick, Vandal, Margaret and J. Delbert, spent time as divorced persons in economic downturn of 1930. In Santa Barbara at the time, census takers might not have caught up with Ollie Everett Rhodes.

Vandal was, with his mother, settled and farming in Colorado by 1940. Second spouse Margaret, then a doctor's assistant, remained as a renter in Portland ... with 2 young daughters. Had he not succumbed at or near the U.S. Embassy in Costa Rica, Vandal might have a Find A Grave memorial. The most diligent among those who voluntarily inventory cemeteries could have clarified, via hyperlink, this relationship web.

Though she is buried in Portland, and he among an extensive Eugene family, childless couple Margaret and J. Delbert have memorials. And the divorced couple are hyperlinked (a diligent Find A Grave caretaker posted and sourced Margaret's Oregonian obit: it references Vandal). J. Del is not linked to second wife Iva, however. Iva shares a fate similar to Gertrude's: though her death certificate lists 'Iva W. Liston,' a grave marker in her parent's Wood plot reads 'daughter.' No surname at all is carved into it. Iva's Find A Grave memorial is not linked to anyone.

Elizabeth (Harriman) Brune bore Charles two sons. These parents are buried where they started a family while tending sheep. They are linked in a virtual, Wasco County, Oregon Odd Fellows Cemetery. Digital flowers also appear at these graves.

|

| Gertrude, with a cousin's daughter. |

Conversational taboo preserves family dignity. It also allows those subsequently afflicted, by disease or societal choices, to be handicapped in isolating belief that they are the first in their family to ever experience a particular hardship. I try to avoid false pride; forgo taking unwarranted, psychic credit for ancestors' meritorious conduct when I find it. So too do I try to avoid shame. Particularly with regard to slave-owning ancestors. I admittedly find it generally challenging not to judge historical figures against contemporary mores.

When I am able to suspend judgment, I actually grow closer to 'what was.' It seems somehow more rewarding than allowing imagination to paint the past.

Those of you who delve concertedly into family history will understand my sense of immersion; of being neck-deep … cross-referencing documents as I'm retaining names and dates. While the image of the log schoolhouse (below) initiated this study, it was an extraordinary observation that prompted me to draft this post.

Today is the centenary of Gertrude's death. Happy New Year, everyone!

This photograph, of a rustic, one-room schoolhouse near Agra, Oklahoma, triggered my labyrinthine investigation. Gertrude is depicted with the letter C.

With deep appreciation for all archivists, particularly those who took time to post the above photographs.

![On reverse: “Oak Dale School, near Agra, Okla. Roy, Hallie & Gertrude Hardesty.” Also handwritten, “George M. Clark, “Artist.” Ripley, corner of [Ok and?] Broad Street.” Author's collection. Image of Oak Dale School, near Agra, Okla.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhQPVO2vk9r1rigFSPNxlYxXyQTKE60adVspsdSuT__SIvk9bG6JcTRyEJ11cvTKdkeAh0cIPhY_jRkCHj42wHPlkptcI9iDC_ctlmXzT6NarPzeSRAJR3t6d3-pOWg2sjxF6rcfvGmGhZn/s640/AgraSchoolFINAL.jpg)